Concerto For Alto Sax And Orchestra

Piano Reduction by Elizabeth Ames - Foreword by Dr. Noah Getz

-

Ships in 1 to 2 weeks

Details

Description

SKU: CF.W2659

Piano Reduction by Elizabeth Ames - Foreword by Dr. Noah Getz. Composed by Henry Brant. Arranged by Liz Ames. SWS. Contemporary. Set of Score and Parts. With Standard notation. 36+12 pages. Carl Fischer Music #W2659. Published by Carl Fischer Music (CF.W2659).ISBN 9780825893179. UPC: 798408093174. 9 x 12 inches. Key: C major. Text: Noah Getz. Noah Getz.

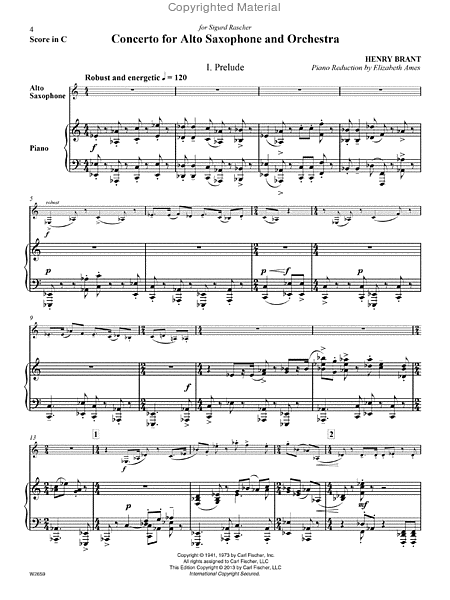

Henry Brant was inspired to write his Concerto in 1941 specifically for the virtuosity of Sigurd Rascher, the incredible performer of the day. He incorporated Rascher's techniques of slap-tongue, flutter-tongue, and extended altissimo, which made the Concerto virtually unplayable by any other saxophonist. After Rascher's last performance of the work in 1953, it would be almost half a century before Brant would authorize another performance with orchestra in 2002, and the fortunate saxophonist was Dr. Noah Getz, another formidable talent. Getz worked closely with Brant in preparation for the performance, and continues to champion the work today. The foreword by Getz provides an excellent overview of the Concerto, and more information is available on his website. While Brant resisted the creation of a piano reduction, Elizabeth Ames has now produced a critical edition, using all available sources. The reduction was thought to be essential in allowing saxophonists to study the work, and in advancing performances of the Concerto with orchestra, as the composer intended.

Henry Brant’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone and Orchestra is a unique and important work in the saxophonerepertoire for several reasons. Written in 1941, this was the first concerto for the saxophone bya significant American composer. It was also the only work for saxophone that included themes basedupon Americana composed at a time when Americana was helping to forge a unique identity for Americancomposers. Brant’s direct ties with Aaron Copland and the Young Composers Group demonstratesthe lineage that this concerto shares with other works by American composers that have become partof the orchestral canon, such as Appalachian Spring and Rodeo. Finally, this concerto was the first toexplore the full range and versatility of extended techniques on the saxophone, including slap-tongue,flutter-tongue, and the use of the altissimo register extending the range to an unprecedented four octaves.By 1940, Sigurd Raschèr had attained an international reputation as a concert saxophonist through frequentsolo appearances with major orchestras as well as participation in leading music festivals. HenryBrant first heard Raschèr perform with the New York Philharmonic that year and was intrigued by theuse of the altissimo register in Jacques Ibert’s Concertino da Camera. Rascher and Brant communicatedbriefly about the prospect of collaborating on a new concerto for saxophone, but the idea didn’t materializeuntil Raschèr scheduled a performance with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra for January 17, 1942.This performance provided the impetus for Brant to begin work on the concerto with a firm date for thepremiere. During a meeting to discuss the new work, Raschèr demonstrated his extended techniques andBrant decided, “I’m going to write a piece for [Raschèr] and it is going to be for the way he plays theinstrument and use all the things that he can do.”1Henry Brant’s program notes for the premiere describe his conception of the new concerto:The Concerto for Saxophone was written in the summer of 1941 and is dedicated to SigurdRaschèr. It is the last in a series of four concertos for diverse instruments with orchestral accompaniment.Mr. Brant writes: “I believe that it is the only concerto ever written for anywind instrument which requires a range of four octaves,” adding that it seems safe to say this,“because the saxophone, in Mr. Raschèr’s hands, is the only known wind instrument capable ofproducing the full four octaves.” The following is from the composer: “The first movement ofthe Concerto is called PRELUDE and indicates good weather. The second movement, IDYLL,is more astronomical. Finally, there is a snide rondo called CAPRICE, complete with cadenza.Generally speaking, this seems to be a ‘country concerto,’ as distinguished from the standardcontemporary model for display pieces, which I regard as ‘city concertos.’2The performance was well received and reviews for the premiere of the concerto were extremely positive.The music editor of the Detroit Free Press stated:The Brant composition was marked by the feeling for humor which is finding such authenticexpression among the moderns. . . . Raschèr is one of the few who have been able to extend therange of the saxophone at least one and a half octaves by the use of harmonics. The ease withwhich he skips through long intervals is something amazing, to say the least. His use of pizzicatiand the development of tone have well established the saxophone as a virtuoso instrument,at least in his own capable hands.”3The Detroit News editor reported: “Raschèr can make the saxophone do everything but recite the Gettysburgaddress. He has a four-octave range and he can play a pizzicato that must be heard to be believed.”4 Rascher would perform the concerto six times between the premiere and his last performance in 1953.In 1945, the concerto was performed with the NBC Symphony Orchestra at the first annual Festival ofContemporary Music at Columbia University. Rascher’s final performance took place with the CincinnatiSymphony Orchestra in conjunction with a recording of the work. The recording was released on theRemington Records label and was re-released on Varèse Sarabande in 1978.By the early 1950s Henry Brant began having some concerns about the orchestral performances of theconcerto, which he blamed on lack of preparation by the ensemble. By then, Brant had heard performancesof the orchestral version multiple times and had revised some of his ideas about the work. In aletter to Raschèr in the early 1950s, Brant provided a short list of the following changes: “(1) All temposshould be if anything slightly on the fast side, (2) Pauses or breaks should be very brief, [and] (3) Ritardandosor any vibrato should be slight.”5 Brant’s desire to revise the work to reflect his compositionalstyle of the time led to the creation of a version of the work for chamber ensemble. Raschèr dislikedBrant’s proposed changes, and refused to play the work when Brant insisted he play only the chamberensemble version. Brant then removed the orchestral and band versions from performance and focusedon performances of the chamber ensemble version.I removed [the orchestral version] from performance because I thought it wasn’tdoing me any good. Slopped off performances where the orchestra isn’t properlyrehearsed. After all, it is not a perfunctory accompaniment. There is detail in the accompaniment.I thought what I want is a carefully worked out performance in whichI could participate.6Henry Brant completed the third version of his concerto in 1970 for solo saxophone or trumpet.Henry Brant’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone and Orchestra was performed for the first time in nearlyfifty years by Dr. Noah Getz with the Florida State University Philharmonic in 2002. This performancecoincided with the re-publication of the orchestral version of the concerto. Henry Brant expressed strongconcerns about releasing a piano reduction of this work during his lifetime because he feared it would beperformed as a stand-alone work substituting for the orchestral accompaniment that he felt was a vitalelement to this concerto. It was decided that a critical edition was needed to allow the saxophone communityto have the opportunity to study the concerto in detail and to expose musicians to this importantwork in the saxophone repertoire. It is hoped that this greater exposure will result in a renaissance of performanceswith orchestra for this concerto and its emergence as a core work in the saxophone repertoire.On a personal note, I have always felt that Henry Brant was the kind of composer you would dream ofcollaborating with: highly skilled at his craft, passionate and a little irreverent. During our lessons hetold me about the time he nearly got kicked out of Juilliard for playing jazz on the piano (20 years beforeMiles Davis tried the same on the trumpet and was told to choose) and suggested that his Americanaperiod was just a way to stay employed as a composer when the only patron hiring was the United Statesgovernment. I will always be grateful to Henry Brant and his wife Kathy for their generosity during mydissertation research. Our impromptu performance of the second movement with him accompanying meon piano is one of my fondest memories from my time visiting and researching in Santa Barbara.

Share

Share