Serious Songs

-

Ships in 3 to 4 weeks

Details

Description

SKU: BR.DV-1089

Composed by Hanns Eisler. Voice; stapled. Deutscher Verlag. Song; Early modern; Music post-1945. Full score. Composed 1961/62. 28 pages. Duration 15'. Deutscher Verlag fur Musik #DV 1089. Published by Deutscher Verlag fur Musik (BR.DV-1089).ISBN 9790200410082. 9 x 12 inches.

The cycle for baritone solo and string orchestra Ernste Gesaenge (Serious Songs) is a work which Eisler began in early 1961 and completed in August 1962. In this work, which was his last (Eisler died on September 6), both the choice and arrangement of the lyrics and the selection of musical approaches give a fairly concentrated idea of the exceptional stylistic breadth which is so characteristic of this important 20th century composer while remaining quite distinct from later postmodern pluralism. The texts and musical structures, so varied in origin and application, are held together by Eislers underlying political convictions - here related to the stunning revelations of the 20th Party Congress of the CPSU - to which Eisler was the only GDR composer to make an explicit response! and the increased hope of a human aspect to Communism.

Talking to Hans Bunge on August 14, 1962, Eisler reported: Arranging the songs took me the most trouble. It took me a year to put seven little pieces into shape. Asked for the meaning of this shape, he said: It is: consciousness - reflection - depression - revival - and again consciousness ... It just must be done that way, otherwise it is not good. One cannot always write optimistic songs ...one must describe the up and down of the actual situations, sing about it and comment on it. For this purpose Eisler used Hoelderlin fragments which he had already set (Asyl (refuge) 1939; An die Hoffnung (to hope) 1943) and a text by Bertolt Viertel, written in 1936 to mark the years of Hitlers dictatorship and already set to music as Chanson allemande in 1953. Now included in the cycle, Traurigkeit (sadness) received a new meaning. Eisler noted: ... now each may seek out the anniversaries that make him sad. The third song Verzweiflung (despair), to an old text by the Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi, set for singing voice and piano by Eisler in 1953 as Faustus Verzweiflung (Fausts despair), also received a new status in the cycle: I need the deep starting-point to jump high - or to raise hopes. The title of the fifth song, XX. Parteitag, was chosen by Eisler himself. Taking a few lines from a poem by Helmut Richter, he had headed them: ... I believe it to be the honesty of the artist to name these things that have been so hard to live through. Sadness and the hope of future happiness permeate the whole work. Autumn is a multiple metaphor: we look back at the past and forward to the future both in the entirely personal sphere and in the overall context of life in society.

Eisler here addresses the particular problem of age. And this general human autumn can also be understood as the autumn of politics. In this endearing conversation with Hans Bunge (November 6, 1961) Eisler said: If the cult of Stalin dies, for instance, that is autumn for Stalin. He falls like the leaves.

And so the Serious Songs cycle is a work Eisler could not have known to be his last and an important testimonial to his general attitude as a political composer. One day after completing the work he told Hans Bunge about his modest music: I love these contradictions. And there is certainly contradiction in my latest work - between the Serious Songs and the present situation. But I believe we must think over the past. Anyone who wants the future must surmount the past. He must purify himself of the past and look clearly and cleanly into the future. I believe we do far too little about that. Perhaps it is the task of an artist - and his task is a very modest one, when we look at the modern world - to see the past truly and sharply and lead it (something for which art is particularly suited) into a future. An artist who does not do this is hopelessly at the mercy of a shabby optimism. Eisler composed the cycle with a view concentrated on the intensity of the singing.

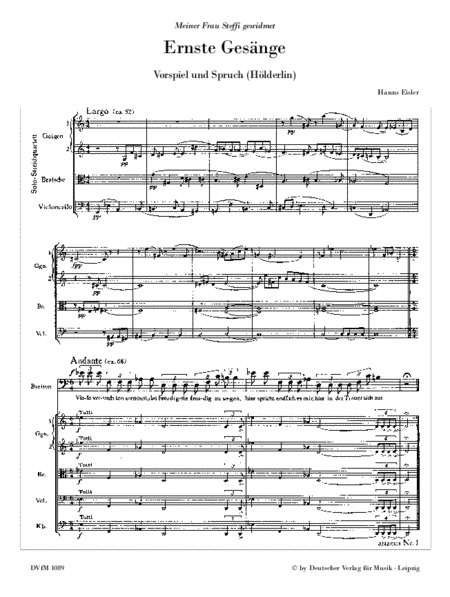

The singing voice and the orchestral writing demonstrate the complexity of free atonality (in Vorspiel and Spruch (prelude and motto) and in An die Hoffnung) alongside the simplicity of tonal writing (in XX. Parteitag, where the Eisler march type comes through). At the end of the work, in the Epilogue and its postlude, the persistent melodic and harmonic beauty points to a more deep-seated ideological insecurity as the sweet promise of the closing instrumental consonance which is not really qualified by the abrupt pizzicato close. The harmonic idyll suggests lack of contradiction. It has something of the other-worldly and unrealistic to it (not Eislers style at all) and yet is involuntarily realistic and from a present day perspective tragic at the same time. It seems that in autumn 1962 Hanns Eisler, despite expressing no verbal doubt in the Communist future, was as an intelligent artist by no means so sure of future happiness.

(Guenter Mayer, translated by Janet and Michael Berridge)

CD:

Gunther Leib (Bar), Dresdner Staatskapelle, cond. Otmar Suitner

CD Musik in Deutschland 19502000

RCA 74321 73558 2

Share

Share